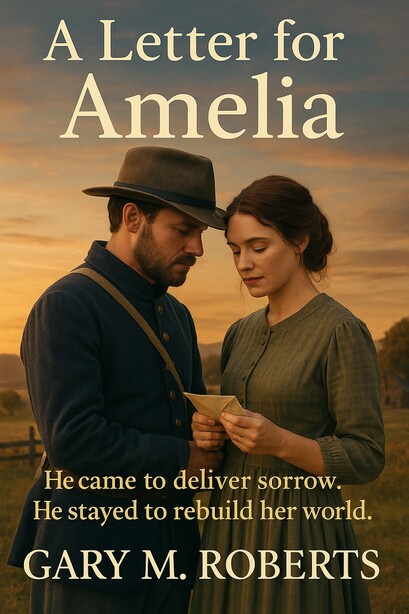

A Letter for Amelia

The war has taken everything from him—his youth, his friends, his home. Now only one thing remains: a letter he must deliver to Amelia, the woman he once loved…and the widow he helped create..

When the guns fall silent after the Civil War, Nathan returns home carrying more than his own wounds. He carries a promise — and a letter. A letter for Amelia Proctor, the childhood friend he once adored, now the grieving widow of the man he persuaded to march off to war.

Amelia has survived loss by hardening her heart. She wants nothing from the man who brought her sorrow — especially not help. But when Nathan arrives, broken and guilt-ridden, determined to restore the farm she and her young son struggle to keep alive, she cannot turn him away.

Day by day, mending fences and planting seeds, Nathan proves himself more than the messenger of bad news. Slowly, trust begins to take root where anger once thrived. As the seasons turn, laughter returns to the farmhouse, and hope stirs in hearts that believed love had no place left.

But letting go of grief is its own kind of battle. Can Amelia open her heart to the man who was once the source of her deepest pain — and can Nathan forgive himself enough to stay?

A tender story of healing, redemption, and the quiet power of love after loss.

Review

The Chrysalis BREW Project Review: Can guilt ever become a form of grace? This question lingers like a ghost in every page — and you’ll only find its answer when you journey through this quietly powerful story. Read more -

Excerpt

Taken from Chapter One:

Chapter One

Prelude

The war had ended, but peace did not ride home with the men who survived.

They returned to familiar fields and empty chairs, carrying ghosts no one else could see. They remembered friends who had fallen, promises whispered over dying lips, letters tucked into cold hands. Nights were the worst — filled with cannon thunder and the faces of the lost.

To live when better men had died was to bear a debt that could never be paid. Some drank, some ran, some tried to rebuild. Others set out again, driven by duty or guilt, to reach the families left behind. They carried letters, keepsakes, and truths that would break hearts.

One such man rides now, a single letter tucked against his chest — a dead friend’s words and a dying promise to deliver them. He tells himself it will be enough. But he knows he carries more than paper: the guilt of surviving and the hope that keeping one last promise might help him find his way home, too.

Chapter One

He woke up because the sound of thunder was gone. It was too silent.

For a moment, he thought he had gone deaf. He lay still under his wool blanket, heart hammering, ears straining for the familiar barrage — the cannon cough, the long, tearing shriek of shot, the rattle of muskets. Nothing came.

Only a thin breeze pushed through the torn flap of the tent and stirred the smell of cold ashes. Somewhere nearby a horse stamped once, its tack giving a dry jingle. Beyond that, the world felt hollow.

He swallowed and heard it, the wet click of his own throat. He could pick out small things again: a drip of water from a canteen, the creak of leather, the low murmur of a man turning over in his sleep. Each sound seemed too sharp, too close, after weeks when every noise was swallowed by thunder.

The silence was not peace; it was raw and tentative, like a wound cooling in the night air. His ears still rang from the day before, a high, thin whine that seemed to prove the world was real. But no cannon followed, no ragged fusillade.

He drew a slow breath, tasting gunpowder ghosts and damp canvas. It was so quiet now that he could hear his own breathing. And that, more than the silence itself, made him shiver.

With a quick glance, he looked to the groundcloth beside him, his eyes searching for someone who was not there. Then it struck him — Wil had been killed yesterday, dropped by a sniper’s bullet before he had time to cry out.

Nathan Stuart rubbed the sleep from his eyes and pushed himself up on one elbow. He listened.

Nothing.

Only the faint clatter of metal pots swaying in the wind outside the tent. No cannon thunder, no crack of rifles — only the thin hiss of morning air. Could it be a ceasefire? He doubted it. Silence in war was rarely safety.

Footsteps broke the stillness. The flap jerked back and a soldier stepped in — little more than a boy, cheeks hollow, eyes too old for his years. He stood stiff as a post, waiting to be addressed.

“Yes, what is it?” Nathan asked, voice still rough with sleep.

“Beg pardon, Lieutenant,” the boy said, staring somewhere beyond Nathan’s shoulder. “Major wants to see you. Wants to see you now, sir.”

“Do you think the Major would mind if I dressed first?”

“I — he didn’t say, sir.”

“Very well. I shall dress first. You are dismissed.”

The boy nodded quickly and backed out, letting the flap fall shut.

Nathan sat a moment, the silence pressing in. Then he drew a breath and began to dress, pulling on his threadbare shirt, fastening his coat. His thoughts turned in uneasy circles. What could Ambrose want at this hour? Another move? God help them if it meant marching again. His feet were raw from weeks of retreat. The men — ragged, hungry, half-shod — had little left to give.

For days they had been falling back, trying to keep ahead of the bluecoats. Morale was crumbling; supplies vanished or broke down on the roads, and desertions bled the ranks thinner every night. North Carolina itself seemed to be slipping away.

Stepping out of the tent, Nathan winced at the April light. A pale morning sun hung over a sky washed clean of smoke. The air was cool and smelled of damp earth and old gunpowder. He shivered — not from the chill but from the eerie stillness.

He straightened his coat and tightened his belt. Even at the ragged end of things, Ambrose expected his officers to look like officers.

The Major’s quarters stood only two tents away, slightly larger, enough to hold a desk and a pair of chairs. Nathan entered as the boy had entered his — silent, waiting to be acknowledged.

Major Ambrose sat behind the small desk, a tin of coffee steaming beside a spread of maps. He looked up, his stern features softened by a faint, almost weary smile.

“Lieutenant Stuart. Come in. Sit.”

Nathan obeyed, caught off guard by the informality.

“Coffee?” Ambrose asked.

Nathan gave a small nod. Coffee was a rare comfort these days, and the Major’s offer unsettled him more than a barked order might have.

Ambrose stood, rummaged in his mess box, wiped a tin mug clean with his fingers, and poured the dark liquid. Nathan took it, warming his hands around the cup as the Major settled back down.

For a long breath, Ambrose stared at the map. When he finally spoke, his voice was low, deliberate — as if each word carried weight.

“Lieutenant Stuart… you are my next in command. We lost Captain Stevens two days ago.” He paused, drawing a slow breath. “You should be the first to know. Word came this morning. General Johnston has surrendered to Sherman. The war… is over.”

Over.

The word struck like a musket ball. For a heartbeat, Nathan could only blink, his thoughts scattering. Over?

“But — but what of General Lee?” he stammered.

“Lee surrendered nearly two weeks ago,” Ambrose said quietly. “It’s done, Stuart.”

Nathan’s throat worked soundlessly. Finally: “What do we do now, sir?”

“The war’s over,” Ambrose said, and his voice softened. “We’ve been granted parole to return home. As an officer, you may keep your sidearm and your horse.” He met Nathan’s eyes — weary, almost fatherly. “Go home, Nathan.”

Nathan rose slowly, boots scraping the packed earth. His mind still reeled from the Major’s words. Almost by instinct his hand lifted, half-formed into a salute, then faltered and dropped to his side. A simple nod seemed enough. Without another word, he pushed aside the tent flap and stepped into the pale April light.

Over.

The word sounded foreign, as if it belonged to some other language. Over. After years of thunder and marching and smoke, it felt impossible that a single morning could bring an ending.

For a heartbeat, he considered calling the men together — telling them, shouting it to the sky, letting the silence shatter under the weight of release. But no. Not yet. His voice would fail him. And the moment felt too raw, too strange for speeches.

He turned instead toward his own tent. Inside, the stillness pressed close. The air smelled of canvas and stale powder. Slowly, he began to gather what little remained: a spare shirt, a worn razor, a few cartridges he no longer needed. His fingers lingered on each item, half-expecting orders to move out to come at any second.

In the corner sat a small wooden box. Wil Proctor’s things. Such as they were. A few faded letters tied with a string, some loose coins he wrapped carefully in cloth. At the top lay an envelope, sealed and addressed to Amelia. With it lay a small tintype: Amelia, looking young and hopeful, her dark eyes steady even in the grainy image.

Nathan lifted the photograph.

Wil.

More than a sergeant under his command — he had been Nathan’s brother in every way but blood. They had fished the same creeks, raced the same horses, shared the same boyish dreams. Even courted the same girl for a season. But it was Wil who’d won Amelia’s heart, and in the end, Nathan had been glad. Wil was the better man — thoughtful, slow to anger, deliberate, where Nathan had always leapt first and paid later.

He traced the edge of the photo with his thumb, a dull ache rising behind his eyes. Wil had steadied him more times than he could count. Now the war had taken him, as it had taken so many.

Nathan closed the box gently, tying the cloth snug around its contents. He would see it to Amelia himself, if he could. She deserved more than a cold notice, and he had promised as much to Wil. And with it, he would deliver Wil’s final letter.

Carefully, he placed the letter beneath his jacket and slipped it into a pocket. Though he could hardly feel the envelope, the weight of it bore on him.

Outside, the camp lay unnervingly quiet — no bugle, no shouted orders, only the flap of canvas and the low sigh of wind through the trees. Somewhere, a coyote yipped and a horse nickered softly, then fell silent again.

Nathan straightened, suddenly aware of the weightless feeling creeping into his chest. Duty — the one constant for four long years — had ended without ceremony. He was a soldier no longer. A man again, though he hardly remembered how to be one.

He drew a long breath, letting the cool air fill his lungs, and stepped out toward whatever life waited beyond this hollow quiet.

Nathan stepped into the weak morning light, the box with Wil’s things tucked under one arm, his bedroll and a few belongings slung over his shoulder. The air felt unsettled, cool against his face. The camp stirred fitfully — men moving with no clear purpose, some crouched over meager fires, others mending gear out of habit more than hope.

A few turned as he passed. They watched him, but no one called out. The silence felt alive, heavy with waiting.

He reached the open space near the company’s cook fire, where a handful of soldiers huddled with tin cups. A thin line of smoke curled upward and vanished against the pale sky. Nathan paused, heart beating hard in his chest.

He wasn’t sure how to do this. He’d given orders a hundred times before — charges, withdrawals, picket shifts — but this was different. This was not a command; this was ending.

He set Wil’s box down gently on a bench and faced them.

“Men,” he said, his voice rough. It wasn’t loud, but every head lifted at once. Faces thin from hunger and sleepless weeks looked back at him — boys and men both, mud-stained, hollow-eyed.

He cleared his throat. “I’ve just come from the Major.” A pause. The silence seemed to lean closer. “Word’s come down… General Johnston has surrendered. To Sherman. The war’s over.”

For a heartbeat, nothing moved. Then someone — Private Ellison, barely seventeen — let out a sharp, disbelieving laugh that died in his throat. Another man swore softly under his breath. One of the older veterans just stared at the ground, eyes wet but unblinking.

“It’s true,” Nathan said, steady now. “We’re granted parole. We’ll be heading home soon. Officers can keep their horses and sidearms. The rest of you will be given papers. No more fighting.”

Still, the men were silent, stunned. The news seemed to take shape slowly, like dawn breaking over fog.

Finally, Corporal Hanks spoke. “That’s it? After all this… just go home?” His voice cracked halfway through.

Nathan swallowed. “That’s it.”

For a moment, no one said anything more. Then the camp began to stir — not cheering, not even talking much, just movement. Men stood, stared at one another, and touched the butts of their rifles as though unsure what they meant now. One sat down hard and put his face in his hands. Another looked skyward, whispering something no one else could hear.

Nathan stayed where he was, watching. He felt hollow and full all at once — relief and grief tangled tight. His eyes found the little box on the bench. Wil would not be going home, but others would. That would have to be enough.

He drew a slow breath and spoke once more, quieter this time but firm:

“Pack what you have. Keep your heads up. We’ll march one last time — but it’s toward home.”

The news spread through camp like smoke on still air — no shouts, no cheers, only murmured words passed from man to man. Each face showed it differently: disbelief, weary relief, sudden tears. Some stared at their boots for long minutes as if waiting to wake. Others moved with a strange urgency, cleaning weapons that would never fire again, folding worn blankets, touching keepsakes tucked in breast pockets.

By afternoon, the Major ordered the men to begin turning in army property that would not be carried home. Cartridge boxes were emptied and stacked, and ammunition was collected in barrels. Broken rifles and splintered bayonets were piled in a low trench and set alight. The acrid smoke curled upward, black and thin, and men stood watching — some silent, some laughing softly, some wiping at their eyes.

Nathan moved among them, saying little. He helped throw a few warped gunstocks into the flames, then stood back, the firelight glinting off his brass buttons. The rifles burned fast once the oil-soaked cloth caught; stocks cracked and hissed in the heat, sending sparks skyward. For years, their lives had been tied to those weapons. Now the army that once felt eternal was vanishing into smoke.

Toward evening, word came that Union cavalry was approaching — not as enemies now, but as keepers of the truce. Nathan’s heart tightened when he saw the first blue coats crest the rise beyond the tree line, sabers glinting in the dying sun.

The Federals rode in slowly, deliberate but not threatening. Their guidons hung limp in the still air. A few of Nathan’s men stiffened, instinctively reaching for muskets that were no longer there, but the Union soldiers only nodded in greeting.

One officer — a young captain, his uniform crisp but travel-worn — dismounted and walked forward, hand extended.

Nathan stepped out to meet him.

“Lieutenant Nathan Stuart,” he said, voice steady though his throat felt tight.

“Captain James Avery,” the Union man replied. His handshake was firm, businesslike, but not unkind. “Sherman’s lines are a few miles east. Papers will be issued in the morning. You and your men are free to return home after.”

Nathan nodded. “We’ve been ready to go home a long while.”

Avery’s mouth twitched, almost a smile. “Most of us have.” He glanced toward the smoldering trench of burned rifles and let out a breath. “Hell of a thing, isn’t it?”

“Hell of a thing,” Nathan echoed.

They stood there a moment — two men who had spent years trying to kill each other, now silent in the cool dusk. Finally, Avery gave a short nod and stepped back, mounting his horse.

The Union column passed quietly through the camp, some riders tipping hats, others only looking on with faces unreadable: no jeering, no triumph, only tired men seeing other tired men.

As darkness settled, campfires flared to life — not the wary, hidden flames of soldiers in the field, but open, steady fires meant to warm and comfort. The smell of salt pork and chicory rose into the night. Somewhere, someone began to hum a tune — low, slow, the kind sung on porches long before war. Another voice joined in, then another, until the song spread, a fragile thing but alive.

Nathan sat beside his small fire, Wil’s box safe at his feet, the letter for Amelia tucked safely in his breast pocket. The night was strange — not free of sorrow, but no longer bound by fear. Tomorrow, they will take their paroles and start the long road home.

For now, he leaned back, listened to the soft singing, and let the quiet wrap around him. For the first time in years, the silence did not feel like waiting for death. It felt, however tentatively, as if life were beginning again.