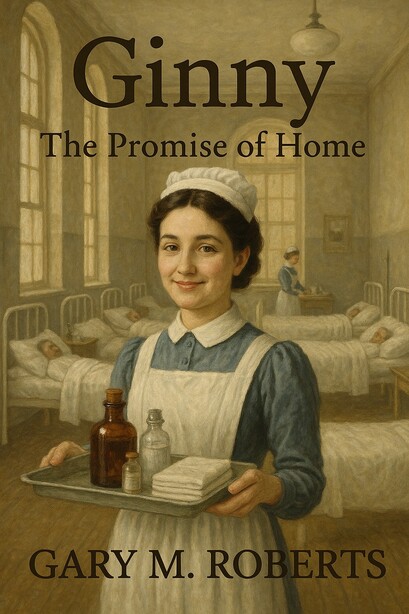

Ginny: The Promise of Home

Two men. Two promises.

One chance at the home she’s always longed for.

Savannah, 1887.

Ginny has survived cruelty, shame, and the kind of childhood that nearly broke her spirit. Now a nurse in Savannah’s grand hospital, she finally tastes independence—and dares to dream of love.

But when her first love unexpectedly returns, the embers of their past ignite with dangerous intensity. At the same time, a new suitor stirs her heart in ways she never imagined—tender, steadfast, and offering the promise of a future untouched by pain.

Torn between two men, Ginny stands at a crossroads. One holds the key to the girl she once was, the other to the woman she longs to become. In a world where passion can both heal and destroy, she must risk everything to discover which man will truly give her what she craves most: a home for her heart.

Torn between yesterday’s flame and tomorrow’s promise, Ginny longs for the one love that feels like home.

Excerpt

Taken from Chapter One:

Chapter One

“Dumb ol’ Ginny got no brains, never had any… Dumb ol’ Ginny got no brains, never had any…”

My cousins sang it so often that the words carved themselves into me, sharp and ugly. For years, I hated them for it—hated the chant, hated the way it followed me like a curse. Now, I’m the one whispering it to myself. A cruel echo.

Dumb, because I let myself believe I could love—and be loved—by a childhood dream. Dumb, because I let love slip through my fingers when it finally came.

I believed Jack Bishop loved me. And maybe he did. But love wasn’t enough to save him from his addiction. The addiction to pain medication took hold of him, reshaped him, until the man who had once been a respected doctor was reduced to a shadow, disgraced and missing.

Then there was Patrick O’Donnell. My pride shoved him out the door before I ever gave him the chance to stay. He wanted to know me—too well, too deeply. And when he started digging into my past, I snapped. I told myself it was an intrusion. I told myself it was betrayal. Truth is, I was scared of what he might find. Of what I might have to face.

But what he uncovered… it changed everything.

Because of Patrick, I know I have a sister—Mae. Flesh and blood. She sees me, really sees me, in a way I’ve never been seen before. She steadies me, anchors me, as if she’s known me her whole life. And she isn’t the only one. There are two more out there. Two sisters I’ve yet to meet.

The thought of them keeps me awake at night. Part hope. Part dread. Family should mean belonging, but what if all they find in me is the broken girl with the cursed chant burned into her bones?

Jack is gone. Patrick walked away. Mae is here, but the others are shadows waiting to take shape. And somewhere in the middle of all this mess, I have to figure out who I am.

Because I’m beginning to understand: my past isn’t finished with me. Not by any means. And the next chapter of my life—the one I never asked for—has already begun.

Next week, I am to finally meet my sisters. The very thought sets my heart to racing—joy colliding with dread until I can scarcely tell one from the other. Mae assures me all will be well. She has been nothing but gracious since our first meeting, patient with my hesitations, quick to laugh, and tender in spirit. Already, I feel as though I’ve known her all my life. She is engaged, she tells me, to a traveling salesman—a Mr. George Carter. I have not met him yet, but by Mae’s description, he is a man of fine manners and steady ambition.

Margaret, she says, lives on the outskirts of Savannah in a whitewashed cottage not far from the marshes. Married these five years, she has three children at her skirts and another on the way. Her husband, Thomas, works for the railroad out at Pooler Station. I passed through there not long ago, the air full of soot and steam, men hurrying along the platforms with shouts and whistles. I wonder now if one of those weary faces belonged to him.

And then there is Mary, the youngest, though still a year my elder. Mae calls her the wild one, though not unkindly. At eighteen she has already seen more of the world than I dared imagine. She has been to Atlanta, bold and bustling, where she walked the very halls of the capitol, itself. She writes, too—articles for the Savannah Evening News and the Savannah Weekly—words of fire and conviction, calling for labor reform, calling for women to be heard in places where we have long been silenced.

I admire her. I fear her. Perhaps both.

And I wonder—how will they take to me? A girl of little learning, who barely completed three years of schooling. A girl who worked more with her hands than with her mind. I have grown in skill these past months, my nursing training advancing under stern tutelage, but I am not yet the finished thing. Not yet the equal of sisters who boast diplomas and accomplishments, who have walked among governors and newspapermen, while I stumble still over letters.

Still, Savannah awaits. Her streets of live oaks and carriages clattering across cobblestones, her harbor restless with ships from far-off ports. Somewhere within that city—among the grand squares and shadowed alleyways—three sisters wait for me.

But blood ties do not always mean love. And in the hush before our meeting, I cannot help but hear that old refrain rise again in my mind, cruel and familiar as the clatter of the trains:

Dumb ol’ Ginny got no brains, never had any…

I press the words down, bury them deep. I must. For next week will change everything.

As for now, I keep myself occupied with the hospital and my studies, pouring every spare hour into tending the endless stream of patients who pass through its doors. Life is steadier these days—dare I admit it, calmer—since Jack’s departure. No longer do I walk the halls with my heart trembling, wondering if I might catch his eye in a hurried glance or feel the brush of his hand in some forbidden moment.

There has been no word of him since. Not a letter, not a whisper. At times, I am tempted to write to his mother, Mrs. Bishop, to inquire after him. Yet I know too well the dangers of such a step. Jack might see it as an overture, a plea for reconciliation, and worse still—word might find its way back to Nettie. My foster mother has never needed much reason to come after me, and I do not doubt she would travel to Savannah if she thought she could wound me further.

So I silence the ache within me, though it cries out to know where Jack has gone. My heart yearns, but my reason holds firm. Some doors, once closed, must remain shut—no matter how loudly the soul knocks against them.

Patrick is another matter entirely. I know where he is—his presence as fixed as the courthouse clock. A few steps down Bull Street, past the clatter of carriage wheels and the smell of horse-sweat and tobacco smoke, stands the police station. If I wished, I could walk through its doors and find him in an instant. Yet that short distance feels heavier than miles of railroad track.

This morning, I nearly did it. I rose earlier than usual, dressed in my plain blue gown, and carried myself into the city under the shade of the live oaks. Savannah was already stirring—the street vendors calling out their wares, the trolley rattling by with its iron wheels screeching against the rails. I kept my eyes forward, but my heart pounded so hard I feared someone would hear it.

At Chippewa Square I stopped, pretending to admire the statue of Oglethorpe, though I had passed it a hundred times before. In truth, I was stalling. The police station was only a turn away. Just one corner. Just one decision.

But then the voices in my head began again—the ones that never seem to rest. It was you who sent him away. You who turned cold when he reached out. You who sharpened your pride into a blade and cut him down.

What if I went to him, only to see that same blade in his eyes now? What if he had long since decided I was not worth the trouble? Worse still, what if he turned me away in front of his fellow officers, their stares burning holes into me?

I lingered there so long, the lamplighter passed by with his ladder, checking the posts though dusk was still hours off. He gave me a curious glance, as if to ask what business kept a young woman rooted to the cobblestones with her hands knotted tight before her. I had no answer, so at last I turned back the way I had come, the station left unseen, Patrick left waiting—though whether for me or for another, I cannot say.

Tonight I tell myself tomorrow will be different. Tomorrow I will find the courage to turn that corner. But deep down, I know the same battle will rage again.

When the morrow came, I did not find myself turning toward the police station, but toward the riverfront. The docks drew me like a refuge, their noise and bustle a strange comfort against the turmoil in my own heart. It had been far too long since I visited the children, since I gathered them around and read aloud to still their restless minds. The docks, for all their smoke and grit, had become a kind of sanctuary to me—a place where my cares eased, if only for a little while.

Bee—Abigail now, as she is called—no longer came. She and Jacob were safe in Mrs. Whittaker’s care. But children are as constant as the tide; where one is carried away, another drifts in.

This time it was a girl, small and slight, no older than Abigail had been when first I met her. Lew told me her name was Naomi. Her mother had taken over my duties at the docks after my injury, and with no one to mind the child, she brought her along, keeping her hidden where she could. Mister Sweeny had discovered her one morning and stormed about, threatening dismissal. But Lew swore it was all performance, for before long, Naomi’s name was added to the ledger and she was given simple tasks—work small enough for her hands.

I caught her watching me that afternoon, her round eyes peeking from behind a crate. When I smiled and spoke her name, she vanished in a flash, skittering back into hiding like a frightened rabbit.

“It’s Miss Ginny, dummy,” Lew called out. “She ain’t gonna hurt ya. She’s the one I told ya about.”

The word struck me like a slap. My jaw tightened before I knew it, and my voice cut sharper than I intended.

“Don’t you ever call her dumb, Lew. Don’t you ever call anyone dumb.”

The boy blinked, startled, his mouth parting in surprise. Seeing the hurt in his eyes, my own softened. I laid a hand on his shoulder. “I’m sorry, Lew. I shouldn’t have spoken so harshly.”

I hesitated, then—for reasons I cannot explain—I let the words come. I told him a little of my past, of Nettie and Gerald, of the cruelty I endured as a child. Not all of it—never all—but enough for him to understand why that word cut so deep, and why I would never let it be spoken carelessly in my presence.

For the first time in years, I felt something ease in the telling. Did my hurt have a purpose?

When I finished speaking, Lew shifted awkwardly on his feet, scuffing the boards with his boot. “Didn’t know, Miss Ginny,” he mumbled. “I won’t say it again.”

“I know you won’t,” I said gently, brushing a stray curl from his brow as if he were my own. He gave me a sheepish smile before darting off to fetch a rope for one of the dockhands.

That left Naomi still tucked away behind her crate, peering out with eyes that shone like river glass. She must have sensed the change in my voice, for this time, when I beckoned, she did not vanish.

“Come now,” I coaxed. “There’s no harm in me. I’ve a book with me today, one the children always like.” I opened the small satchel I carried and showed her the worn little volume. The gilt on the cover had long since faded, but the words inside remained as bright as ever.

Slowly, cautiously, Naomi crept forward, her bare feet whispering against the boards. She stopped just beyond my reach, her thin arms folded tight across her chest.

“Would you like to hear a story?” I asked.

She nodded—barely, but it was enough. I settled myself on an overturned barrel, opened the book, and began to read. Within minutes, Lew returned, and then two others joined, until I found myself surrounded by half a circle of small faces, all listening as if the world outside the page had ceased to exist.

Naomi edged closer by degrees, until at last she sat cross-legged on the boards at my feet, chin lifted toward the sound of my voice. When I glanced down, she startled, but I offered her a smile, and to my delight, she did not retreat.

By the time I closed the book, the sun had dipped low, the water gilded with gold. Naomi remained at my side, silent but no longer fearful, her small hand resting lightly against my skirt as if she had forgotten it was there.

It struck me then—these children, these overlooked souls of the docks, were as much my family as any blood relation I had yet to meet. Each of them carried scars, some seen, some hidden. And perhaps, in offering them a story, a kindness, or simply a safe place to rest, I was finding a way to heal my own.

The next day, as soon as my duties were over, I returned to the docks. Naomi was waiting. Not beside her mother as I expected, but at the very edge of the pier, her toes curled against the wood as if she meant to leap into the river, itself.

“You’ll fall if you lean so far,” I warned gently.

She turned with a quick, sly smile. “I wasn’t gonna fall. I was lookin’ for the ships. They carry letters from everywhere, don’t they?”

I laughed softly, surprised by her boldness now. “Yes, from everywhere. Charleston, New Orleans… even across the ocean.”

Her eyes lit at the thought, but then dimmed. “If they bring letters, they can take ‘em too, can’t they?”

I knelt to meet her gaze. “Yes, Naomi. They can take them too.”

She hesitated, biting her lip. Then she whispered, “Could you help me write one? I don’t know how, not proper, but Mama says you do.”

It was such a simple request, yet I felt the weight of it settle over me. Letters mean connection, and connections mean secrets uncovered. Who did she wish to reach? A father lost to the railroads, a brother gone to war, or someone else entirely?

I agreed, of course. How could I not?

“Dumb ol’ Ginny got no brains, never had any… Dumb ol’ Ginny got no brains, never had any…”

“Don’t you ever call her dumb, Lew. Don’t you ever call anyone dumb.”